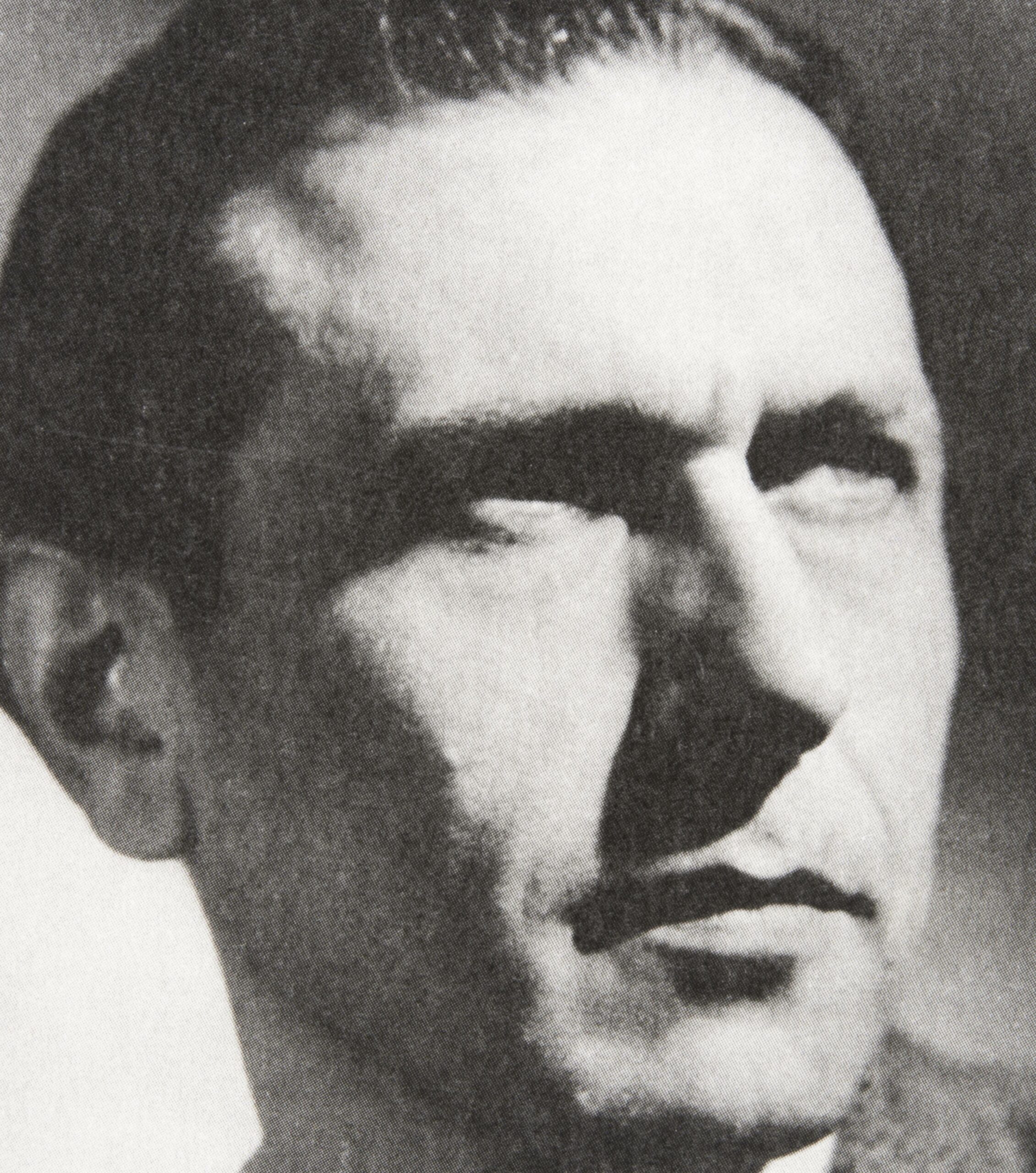

On Reflection

To a Greek poet

The invaders you wait for outside the poem

are behind you in the city:

the miller pilfering weights of grain,

the one who stole the wheel from the temple,

the merchant with his stack of deeds,

the judge with greasy hands,

the rabid lawyer,

the officer of polished medals,

the soldier with a shadow on his lip

thin and naked in a stranger’s bed,

the informer, the lowest, the lowest,

who submits reports in the ink of the flag.

You wait for them in the upper city,

with your anthems,

with lofty expectations,

with foam in the mouths of spokesmen,

with scales of beguiling balance,

with banners of the battle,

invaders are behind you

in the bazaar, in the castle.

Al-Hamidiya, how will you speak

to the crescent of Ramadan this year?

The invaders, mothers wait for them

in the fields with jugs of milk

and fathers carry plates of food

and grandmothers bring embroidery.

The invaders, who stir the thoughts of women

and turn water to a burning trickle,

pass through your waking hours

and pass through your sleep.

Thus imagination triumphs over the city,

clouds of smoke over the mountains,

the sleepers in the honey of ideas triumph

over those who punch the salt

and over transients in the blood of night;

how the sleeping soldier triumphs

over he who sits awake,

how the coward who runs triumphs

over the stalwart who stays to hold the wall.

The vehement orator, the flexible politician,

the scandalous consul, all sing together

to the belly dancer tonight,

Long live the homeland!

Long live the homeland!

No one asks for photos of the victims,

nor the names of the wounded and the missing.

They throw the dead and injured on carriages

and dump on them piles of laurels and barley bags.

The invaders you wait for inside the poem,

in the shadow, are with you in the marrow of the city.

Tout Compte Fait

à un poète grec

Les envahisseurs que tu guettes hors du poème

sont derrière toi dans la cité :

le meunier qui triche sur le poids du blé,

celui qui vola la roue du temple,

le marchand avec son tas d’actions,

le juge aux mains graisseuses,

l’avocat enragé,

l’officier aux médailles qui luisent,

le soldat dont la lèvre s’ombre d’un duvet,

mince et nu dans le lit d’une étrangère,

l’informateur, le plus vil de tous,

qui écrit des rapports de l’encre du drapeau.

Tu les attends dans la ville haute,

avec tes hymnes,

et de nobles attentes,

de l’écume à la bouche des orateurs,

de trompeuses balances,

des bannières de bataille,

les envahisseurs sont derrière toi

dans le bazar, dans le château.

Al-Hamidiya, comment parleras-tu

au croissant du Ramadan cette année?

Les envahisseurs, les mères les attendent

dans les champs avec des pots de lait

et les pères portent des plats de nourriture

et les grand-mères, des broderies.

Les envahisseurs, qui excitent les pensées des femmes

et font de l’urine un filet brûlant,

traversent tes heures de veille

et traversent ton sommeil.

Ainsi l’imagination triomphe de la cité,

nuages de fumée par-dessus les montagnes,

les dormeurs dans le miel des idées triomphent

sur les brasseurs de sel

et ceux qui passent dans le sang de la nuit ;

comme triomphe le soldat qui dort

sur celui qui reste assis éveillé,

comme triomphe le lâche qui s’enfuit.

A Late Party

I hadn’t noticed they were dead –

the party-goers thumbing empty glasses –

until she rushed through their chatter

with a drip of wine down her sugary blouse.

Is she now stripped to her bra at the sink,

dabbing the stain with paper towels?

And tonight, when she is laughing

and naked, who is it she will lie with

while we pale employees of the payroll

are bloodless, adrift in our rooms?

Fin de Réception

Je n’avais pas vu qu’ils étaient morts -

les invités de la fête, un verre à la main -

jusqu’à ce qu’elle ne file à travers leur rumeur,

une goutte de vin sur son corsage clair.

Maintenant, en soutien-gorge à l’évier,

tamponne-t-elle la tache avec des serviettes en papier?

Et ce soir, rieuse

et toute nue, dans quel lit va-t-elle coucher,

tandis que nous, employés du registre,

dérivons, pâles, vers nos chambres?

A Black Balloon

After only a week can I say, I was in London or

When I was in London or Oh… it was beautiful,

and add, in a snappy way, so cold and so ugly?

I’ll conclude, Time passes like a sickness on a bridge.

Is a week enough for someone like me to tick off

the afternoon’s hallucinations and really test a city,

find a way through Siamese streets and read

a few pages of Orwell in a crummy hotel in Paddington?

The winter cold leads me strolling indoors.

I will ask Reception to switch my room

for one of those that overlooks the murky canal.

London might as well be a cemetery in the sea.

Afternoons seem to sum it up pretty well;

the black cabs scowl in the road and the men

that were heroes of El Alamein wear starched collars

and rush to marvelous parties where everyone dances.

On the road, in the gray-green park, is a pretty secretary

pushing her boss on a swing. His neck is flushed and full,

as though pumped with all the blood of Indians

and his pale hand grips the string of a black balloon.

Un Ballon Noir

Une semaine suffit-elle pour répéter, J’étais à Londres, ou

Quand j’étais à Londres, ou Oh… c’était bien,

ajoutant vivement, très froid et laid?

En somme, Le temps passe comme une maladie sur un pont.

Une semaine suffit-elle à quelqu’un comme moi pour dépasser

les hallucinations de l’après-midi et tester une ville,

trouver son chemin dans des rues siamoises et lire

quelques pages d’Orwell dans un hôtel minable à Paddington?

A cause de l’hiver, je piquenique à l’intérieur ;

inévitablement, il faut repousser les choses.

Je vais demander qu’on me donne plutôt

une chambre surplombant le canal.

Et si Londres n’était qu’un cimetière du fond des mers?

Les après-midis illustrent assez bien la situation :

les taxis sont noirs et froncent les sourcils,

les héros d’El Alamein ne sont plus que des cols amidonnés

se ruant à des fêtes où tout le monde danse.

Sur la route, dans le feuillage vert-de-gris, une jolie secrétaire

pousse son patron sur une balançoire. Les veines de son cou sont écarlates,

comme s’il avait bu tout le sang des Indiens

et sa main pâle étreint la cordelette d’un ballon noir.

Pillow Talk

before the guillotine before sleep

before the hand that plucked is lifted

before sleep

and a swarm of light

before sleep

and the burning of the colours

flaps blooms

and curls from heat

breaks from the blood

and settles untouched

before sleep before fire

before the island cracks from the shore

Ce que dit l’oreiller

La guillotine précède le sommeil

avant de savoir que la main

a laissé ce qu’elle tenait glisser comme du feu

avant le sommeil

avant l’éclat de la lumière

dans le silence

et l’embrasement des couleurs ;

avant le sommeil

un oiseau bat des ailes

les ouvre quand il s’écroule

et bat des ailes encore

impalpable disparaissant

dans d’amoureux voiles blancs,

dans l’explosion de sang

d’un autre amour ardent

avant d’être touché

avant la fuite et l’exil.

Damascus

In this little bag that bumps at my shoulder,

I carry down a question bigger than Mount Qasioun.

The entrance to Damascus is locked and checked;

out of reach, the city’s stashed its heart away.

Boys who killed themselves left balls of wool;

I tie my door, knit jumpers for the dead, wait.

Damas

Dans ce petit sac comme une bosse à mon épaule,

je porte un question plus grande que le Mont Qasioun.

L’entrée de Damas est fermée et contrôlée :

hors d’atteinte, la ville a caché son coeur.

Des garçons qui se sont tués ont laissé des balles de laine :

Je ferme ma porte, je tricote des pulls pour les morts, j’attends.

Poèmes traduits de l’arabe vers l’anglais par Tom Warner, et de l’anglais vers le français par Marilyne Bertoncini