Les lunettes de lecture

J’étais arrivée en avance pour notre rendez-vous et j’attendais mon amie autrichienne au café. Elle habitait au Japon depuis plusieurs années mais nous parlions toujours anglais entre nous.

Nous avions rendez-vous presque chaque semaine dans le même établissement. Lors de nos rendez-vous, j’arrivais toujours avec un peu d’avance et j’écrivais un poème dans mon calepin. C’était une habitude automatique. Quand mon amie arrivait, j’enlevais mes lunettes de lecture et posais mon stylo sur la table. Ma tasse de thé était placée juste devant moi.

A chacune de nos rencontres, mon amie me posait la même question. “Comment peux-tu écrire des poèmes?” Chaque fois qu’elle me posait cette question, je me demandais, “Pourquoi ne serais-tu pas capable d’écrire des poèmes?” Ce jour-là, nous décidâmes d’étudier ma paire de lunettes sur la table et d’écrire les sentiments qu’elle nous inspirait.

Mon amie avait beaucoup plus d’idées que moi sur mes lunettes et me dit, “Une copine m’a dit l’autre jour, ‘tes lunettes ne te vont pas.’ Mais j’aime ces montures-ci. Je voudrais essayer tes lunettes. Je me demande si elles m’iront.” Je lui dis, “Mets cela sur le papier.” Je lui donnai une feuille de papier et un stylo que j’avais sur moi. L’air perplexe, mon amie dit, “Je ne peux pas l’écrire. »

Et toi, qu’as-tu ressenti à l’égard de tes lunettes?” me demanda mon amie. J’écrivis un texte intitulé Les lunettes de lecture que je lus à haute voix.

Les lunettes de lecture

Mon grand-père

redemanda à ma grand-mère,

“Cherche mes lunettes.”

Ma grand-mère dit,

“Tu n’entends déjà pas bien

mais tu oublies tout.”

Mon grand-père dit,

“Ta grand-mère me gronde toujours.”

Il s’essuya les yeux.

Grand-père, est-ce que tu pleures?

Non, c’est le poivre rouge qui me pique les yeux.

J’avais écrit quelque chose que je n’avais encore jamais ressenti. Je ne comprenais pas comment une paire de lunettes de lecture avait inspiré ces lignes.

Quel espace sépare-t-il le monde des faits de celui de l’ ‘imagination? Et que dire de celui qui sépare l’ imagination du stylo? Je trouvais que les idées de mon amie étaient un poème en soi. Je lui dis, “Ce que tu viens de partager avec moi est un poème.” Mon amie secoua la tête et reprit, “Je n’ai rien dit de plus que de simples faits. Ce deviendrait un poème si c’était versifié et lu à haute voix.” Je ne voulus pas la contredire.

Une nappe blanche recouvrait notre table, avec des serviettes du même tissu. Un palmier nain en pot croissait tout près. Ses feuilles frémissaient sous la brise créée par le ventilateur de plafond. Un tableau représentant un homme habillé de blanc était accroché au mur. Il portait un grand panier posé sur son turban et il était nu-pieds. De temps à autre me parvenait la voix d’un homme qui prenait les commandes de thé. Il me semblait que chaque consommateur se portait témoin et écoutait notre conversation.

Si un poème n’existe que dans le coeur, n’est-il pas un poème? Etait-ce par gêne ou par fierté que mon amie n’avait pas pris mon stylo? Je regardai les serveurs plier et disposer les serviettes sur les tables. Soudain, je sentis qu’un poème existait dans leurs mouvements. Le rire discret des consommateurs m’était une musique.

En reliant les objets et les sons quotidiens, les gens créent quelque chose de merveilleux qu’ils n’ont encore jamais ressenti. Chaque instant de la vie existe dans une harmonie, comme un tableau. Nos oreilles saisissent la musique des sons fugitifs de la vie quotidienne. Je regardai la feuille de papier blanche devant mon amie. Figée, silencieuse, la scène devant moi tentait d’entrer dans ma mémoire telle une illusion d’optique. L’espace entre faits et imagination et imagination et stylo s’effaçait. Même s’il n’est pas écrit, un poème existe.

“Comment peux-tu écrire des poèmes?” Si l’on me posait la question maintenant, je pourrais dire, “Le fait d’être ici, n’est-ce pas un poème en soi?” Avec une feuille de papier et un stylo à côté de nous, dans un silence total, j’écouterai les sons discrets de la vie. Mon amie enleva ses lunettes et essaya les miennes. Elles lui allaient vraiment bien. Je les mis dans mon sac. Lorsque nous sortimes du café, je sentis que notre amitié s’était approfondie. Depuis, mon amie a cessé de me demander, “Comment peux-tu écrire des poèmes?”

**********

Reading Glasses

by Shizue Ogawa

Translated by

Soraya Umewaka

I arrived earlier than our rendezvous time and waited for my Austrian friend at a café. She lived in Japan for many years but we spoke to each other in English.

Almost every week we would meet at the same place. Whenever we would meet, I would always arrive a little early, and I would write a poem in my pocket notebook. That wasn’t a conscious habit. When my friend arrived, I would remove my reading glasses, and rest my pen on the table. My teacup was positioned right in front of me.

Every time my friend and I would meet, she would ask me the same question, “How is it that you can write poems?” Every time she asked me that question, I asked myself, “Why wouldn’t you be able to write poems?” That day, we decided to look at and write what we felt about my glasses on the table.

My friend had many more thoughts than me on my glasses and told me, “A friend said to me the other day, ‘Your glasses do not suit you.’ But I like these frames. I want to try your glasses. I wonder if they will suit me.” My Austrian friend said, “That is something that actually happened.” I told her, “Write it on this piece of paper.” I gave her paper and a pen that I had on me. My friend said, “I can’t write that down,” and looked perplexed.

“What did you feel about the glasses?” My friend asked me. I wrote a text that I titled, “Reading Glasses.” I then read it out aloud.

Reading Glasses

My grandfather

asked again my grandmother,

“Look for my glasses.”

My grandmother said,

“Your hearing is bad

but your memory is terrible.”

My grandfather said,

“I’m always scolded by your grandmother.”

He wiped his eyes.

Grandpa, are you crying?

No, red pepper is stinging my eyes.

I wrote something that I had never experienced before. I didn’t understand how a pair of reading glasses inspired these lines.

What space exists between the world of ‘facts’ and the world of ‘imagination’? How about the space between ‘imagination’ and ‘a pen’? I felt that my friend’s thoughts were a poem in itself. I told her, “What you just shared with me is a poem.” My friend shook her head and continued speaking, “What I just said are simple facts. It only becomes a poem when it’s written with beautiful rhythms and if it’s read.” I wouldn’t argue with her.

A white tablecloth covered our table with napkins made out of the same material. Helm palm grew in a flowerpot. The leaves collected wind generated from the ceiling fan and slightly stirred. A painting of a man wearing white cloth hung on a wall. He carried a large basket over his turban and was barefooted. I could hear intermittently the voice of a man taking tea orders. I felt that everyone in the café acted as a witness and listened to the conversation between my friend and me.

If a poem only exists within the heart, is it not a poem? Did my friend not take my pen because she felt self-conscious or maybe it was her pride? I watched the waiters folding and arranging the napkins on tables. Suddenly, I felt that a poem existed within the movements of the waiters. The gentle laughter of the customers was music to my ears.

When ‘people’ link together daily objects and sounds, they will create something amazing that they had never experienced before. Every moment in life exists in harmony like a painting. Our ears catch the music of fleeting sounds of daily life. I stared at the blank piece of paper in front of my friend. The scene in front of me stood still, and silently attempted to enter my memory, an optical illusion. I started to feel that the gap between ‘facts and imagination’ and ‘imagination and a pen’ ceased to exist. Even if it is not written, a poem still exists.

“How is it that you can write poems?” If I were asked now, I would be able to say, “Us being here, isn’t that a poem in itself?” With a paper and pen beside us, in complete silence, I will be able to listen to the subtle sounds of life.

My friend removed her glasses and tried my glasses. They really suited her. I put away my glasses in my bag. When we left the café, I felt that our friendship had deepened. Since then my friend stopped asking me, “How is it that you can write poems?”

***********

め が ね

小 川 静 枝

私は待ち合わせの時間より、早く着いた。喫茶店でオーストリアの友人を待った。友人は長く日本に住んでいた。私たちの共通の言語は、英語であった。

私たちは、ほぼ1週間に1度、同じところで会った。その人と会う時は、私はいつも早めに着き、手帳に詩を書いていたようだ。私はそれを、意識してはいなかった。友がやって来た時、私はめがねをはずし、ペンを置いた。ティーカップが目の前にあった。

友人は私に会うたびに、同じ疑問を投げかけた。それは「なぜ詩が書けるか」ということであった。私はそれを聞くたびに、「なぜ書けないか」という疑問を抱いた。その日、「テーブルの上に置かれためがねを見て何を感じるかを、お互いに書いてみよう」ということになった。

友人は私より多くのことを思い、語ってくれた。「私は友だちに、『あなたのめがねは、似合わない』と言われた。でも私はこのフレームが好きだ。あなたのめがねをかけてみたい。それは私に似合うかしら」という内容であった。オーストリアの友人は、「実際にあったことを私に告げた」と言った。私は「それをこの紙に書いて」と頼み、手元にあった1枚の紙とペンを渡した。友人は「書けない」と言って、困惑した表情をした。「あなたは何を感じたの?」と、友人が尋ねた。私は、次のことを紙に書いていた。題は「めがね」であった。私は、これを声に出して読んだ。

め が ね

おじいちゃんは

また おばあちゃんに

「めがねをさがして」と頼んだ

おばあちゃんが

「あなたは 耳が悪いばかりではなく

物忘れもひどい」と言った

おじいちゃんが

「おばあちゃんに しかられてばかりだ」と言って

目をふいた

おじいちゃん 泣いているの?

いいや とうがらしが目にしみた

私は、1度も経験したことがないことを書いた。なぜめがねから、これらの行が生まれたのかは理解できなかった。

「事実と想像の間」には、一体何があるのだろう。「想像とペンの間」には何が?友人の考えたことは、それ自体が詩であると思われた。私は、「あなたが語ってくださったことは、詩ですね」と言った。友人は、頭を横にふった。「私が言ったことは事実に過ぎない。美しい音で書かれなければ、そして読まれなければ詩にはならない」と、ことばを続けた。私はあえて反論はしなかった。

私たちのテーブルには、白いクロスがかけられ、クロスと共布で作られたナプキンが置かれていた。植木鉢にはシュロが植えられていた。天井のサーキュレーターから流れてくる風を受けて、葉がかすかに揺れていた。壁にかけられていた絵には、白い布を体に巻いた男性が描かれていた。ターバンの上に大きなバスケットをのせていた。裸足であった。紅茶の注文を取る男性の声が、時折り聞こえた。友人と交わした会話を、この店のすべてが証人として、聞いているように感じられた。

詩は、心にあるだけでは詩ではないのだろうか?友人は、恥じらいのために、あるいは誇りのために、ペンを取ろうとしなかったのであろうか? 私は、ナプキンをたたみながら、テーブルに並べてゆく店員を見ていた。突然、私はその店員の動きの中に、詩が存在すると感じた。店の客のかすかな笑い声が、音楽として耳に響いた。

「人」が日常の品々や音を互いに結びつけ、これまで味わったことのない驚きを生み出す。生活の一瞬一瞬は、絵画のような調和の中にあるのだ。私たちの耳は常に移ろう生活の音を、音楽としてとらえているのだ。

私は友人の前に置かれた、何も書かれていない紙を見つめた。目の前の情景が静止し、静かに私の記憶に入り込むような錯覚を覚えた。「事実と想像」、そして「想像とペン」の間には、いかなる溝も存在しないと感じ始めていた。書かれなくても、詩は存在する。

「なぜ詩が書けるの?」 今ならその問いに、「私たちがここにいることが、詩ではないかしら」と答えることができるであろう。そして紙とペンを脇に置いて、完成された静けさの中で、かすかに聞こえる生活の音に耳を澄ますであろう。友人は自分のめがねをはずして、私のめがねをかけてみた。それはとてもよく似合っていた。私はめがねをかばんにしまった。私たちがその店を出る時、友情がさらに深まったことを感じた。友人はそれ以来、「なぜ詩が書けるの?」と私に尋ねなくなった。

- L’Effacement, poème de Lise Gauvin & 10 photographies de Wanda Mihuleac - 4 mai 2019

- Michèle Duclos, Un regard anglais sur le symbolisme français - 1 mars 2018

- Éternel recommencement ou histoire croisée ? Les paradoxes du postmodernisme américain - 30 juin 2017

- Il y a quarante ans, Patrick Modiano…, poème d’Anna Frajlich traduit et présenté par Alice-Catherine Carls - 6 décembre 2014

- La poésie de Charles Wright - 23 novembre 2014

- Michael Harper, paroles en archipel - 27 octobre 2014

- Poèmes choisis par Alice-Catherine Carls - 15 septembre 2014

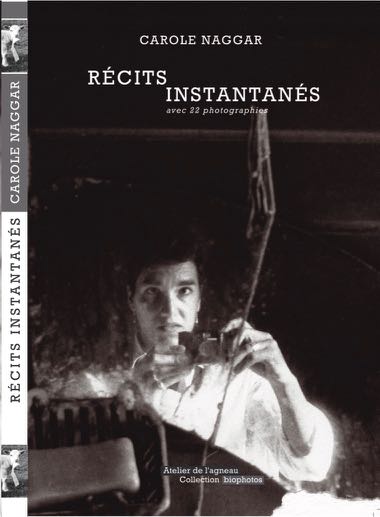

- La poésie de Shizue Ogawa - 7 juin 2014

- La poésie d’Anna Frajlich - 19 mai 2014

- La poésie de Joanna Pollakowna. - 26 avril 2014

- Les lunettes de lecture - 21 février 2014